[h1] [/h1][h1]Color of Fresh Meat: The Basics[/h1]

The information from the above post was taken from the source below and is in the public domain:

Posted on

23. September. 2009 by Chris Raines

By Christopher R. Raines

The color of fresh meat is considered one of the most influential factors related to fresh meat purchasing decisions. To many consumers, it can be a troubling thing, to go to the self-serve retail meat case and see one steak that is a bright, cherry-red color (packaged on a tray and wrapped in film) and right beside it is a dull, purple appearing steak (packaged in vacuum). Why the color difference? Even if those two steaks were cut from the same loin, they can appear very differently.

The reason for this apparent difference is probably due to how the meat was packaged. In order for meat to “bloom” (meat industry jargon for turning from purple to red), exposure of the primary pigment in meat (myoglobin) to oxygen is needed (*meat color is a super-complicated thing; for now, let’s presume oxygen is the only substance that can cause meat to bloom; I’ll delve into others in later entries). Thus, if fresh meat (“fresh meat” meaning steaks, chops, ground beef, etc. — not salami, bacon, ham…) is packaged in a way that lets it contact oxygen (this is how most meat in self-serve meat cases are packaged), or displayed fresh at the meat counter, it should look red. Problematically, once the steak is cut and exposed to air, oxidation (going rancid or “off”) may begin. To mitigate oxidative deterioration and essentially keep meat fresher longer, there is vacuum packaging (some folks use the blanket term “Cryovac” in lieu of vacuum), in which meat is packaged without oxygen, and thus the fresh meat would appear a dull, purplish color. Vacuum packaging is pretty handy – take the air away, and meat will keep (frozen orrefrigerated) longer.

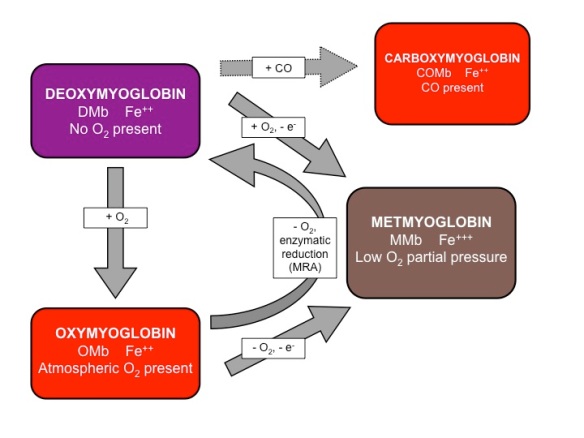

Below is an illustration of the relationships among different states of myoglobin in fresh meat:

Forms of myoglobin, adapted from Mancini & Hunt, 2005

There is a lot happening in this diagram! (1) Let’s start with DEOXYMYOGLOBIN in the upper left, which appears purplish. This is the color of meat when myoglobin is in its native state, or immediately after cutting and before blooming. For example, purple is the color of meat in the middle of a steak (i.e., When you cut across a raw, fresh steak that’sred on the surface, it should be purple in the middle. If you let the steak sit for a bit exposed to air, that color will change, or bloom, to cherry red.) (2) In the presence of oxygen (better referred to as oxygenation), fresh meat blooms and turns its characteristicred color. This form of myoglobin is called OXYMYOGLOBIN. After prolonged exposure to oxygen, (3) we then have METMYOGLOBIN, which appears brown. If you’ve ever been to the grocery and see brown spots on the “Reduced for Quick Sale” fresh meats, those superficial blemishes are METMYOGLOBIN. (Those little brown spots may not look appealing, but may not mean the meat is not safe to eat after cooking. However, if you’veany reason to believe it’s not safe – such as smells spoiled - don’t eat it!) After the meatoxygenates and turns red, it will eventually oxidize and turn brown.

Getting into the chemistry of the matter, the state of the iron in myoglobin (the heme pigment – this is the iron than makes red meat “high in iron”) is a determining factor to fresh meat color. DEOXYMYOGLOBIN and OXYMYOGLOBIN contains iron in the ferrous (Fe 2+) state and METMYOGLOBIN contains iron in the ferric (Fe 3+) state. Let’s dig deeper into this ferrous/ferric business…

Electron management is the key to meat color management. As outlined above, the difference between desirable, red fresh meat and undesirable, brown meat is oneelectron. Yep, one. Follow the arrows in the diagram, and you can see how the different color forms relate to each other. A classic example of these color dynamics in action that you may have observed yourself are the different colors of beef present in one ground beef vacuum chub. Meat may look red or purple on the outside, but have a brown, muddyappearance in the middle. That’s totally okay — look above at the color cycles. The red(bloomed) ground beef was put into a vacuum package, and before it turns purple, it turnsbrown. Since the beef has gone through this natural color cycle a few times (from purpleto red to brown to purple…), the enzymes in the meat that allow for this cycle to continue are worn out (those guys tucker out pretty quickly and easily). Thus, the meat may stop atbrown and stay there. That’s just how the color dynamics work — it does not necessarily mean the beef has gone bad.

I’m working an entry as to why cooked beef color is not a good indicator of doneness, and why a meat thermometer should be used to ensure that any ground meat is cooked to 16o°F. (UPDATED: cooked ground beef color post here) There’s another thing happening in the upper right of the myoglobin color forms diagram —CARBOXYMYOGLOBIN. I’ve left that out of the color dynamics explanation for now, but will address it soon. (UPDATED: Carboxymyoglobin post here)

From "Meatblogger.org"

[h1]Blog Policies[/h1]

Advertising - Advertising is not allowed on wordpress.com hosted blogs. Please do not email me and ask to advertise your product. Furthermore, this is a Pennsylvania State University-affiliated educational blog, not a platform for selling products.

Comment Moderation – As much as I value comments and opinions, comments are moderated for this blog. This is a Pennsylvania State University-affiliated blog and I must work to maintain the integrity and respect of the institution.

Copyright - I have placed this work in the public domain and I disclaim all copyright to the work. I have created this work to benefit the greater good, with specific emphasis on the agriculture community. This work may be freely reproduced, distributed, transmitted, used, modified, built upon, or otherwise disseminated by anyone for any purpose, commercial or non-commercial, and in any way, including by methods that have not yet been invented or conceived.

Please respect the copyright of authors whose material I excerpt for educational purposes. My copyright policy exists for my original work only, not excerpted work from other authors. I make every attempt to clearly identify excerpted works in my posts and podcasts, and if you are in doubt, ask me. I can always be reached at [email protected].

Guest Posts – I welcome guest posts! If you wish to guest post, drop me a note at [email protected]. I ask that guest posts are relevant to agriculture, specifically meat science. Please keep the post credible, research-based, and objective.

Official Communication – This blog does not represent official communications from The Pennsylvania State University or Pennsylvania State University Extension. The views expressed herein and of guest authors do not necessarily reflect the views of The Pennsylvania State University, Pennsylvania State University Extension, or of any other individual university employee.

I reserve the right to amend, append or otherwise modify these policies.

The information from the above post was taken from the source below and is in the public domain:

Posted on

23. September. 2009 by Chris Raines

By Christopher R. Raines

The color of fresh meat is considered one of the most influential factors related to fresh meat purchasing decisions. To many consumers, it can be a troubling thing, to go to the self-serve retail meat case and see one steak that is a bright, cherry-red color (packaged on a tray and wrapped in film) and right beside it is a dull, purple appearing steak (packaged in vacuum). Why the color difference? Even if those two steaks were cut from the same loin, they can appear very differently.

The reason for this apparent difference is probably due to how the meat was packaged. In order for meat to “bloom” (meat industry jargon for turning from purple to red), exposure of the primary pigment in meat (myoglobin) to oxygen is needed (*meat color is a super-complicated thing; for now, let’s presume oxygen is the only substance that can cause meat to bloom; I’ll delve into others in later entries). Thus, if fresh meat (“fresh meat” meaning steaks, chops, ground beef, etc. — not salami, bacon, ham…) is packaged in a way that lets it contact oxygen (this is how most meat in self-serve meat cases are packaged), or displayed fresh at the meat counter, it should look red. Problematically, once the steak is cut and exposed to air, oxidation (going rancid or “off”) may begin. To mitigate oxidative deterioration and essentially keep meat fresher longer, there is vacuum packaging (some folks use the blanket term “Cryovac” in lieu of vacuum), in which meat is packaged without oxygen, and thus the fresh meat would appear a dull, purplish color. Vacuum packaging is pretty handy – take the air away, and meat will keep (frozen orrefrigerated) longer.

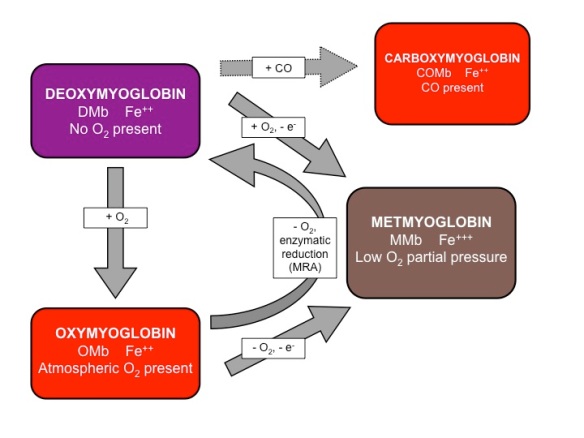

Below is an illustration of the relationships among different states of myoglobin in fresh meat:

Forms of myoglobin, adapted from Mancini & Hunt, 2005

There is a lot happening in this diagram! (1) Let’s start with DEOXYMYOGLOBIN in the upper left, which appears purplish. This is the color of meat when myoglobin is in its native state, or immediately after cutting and before blooming. For example, purple is the color of meat in the middle of a steak (i.e., When you cut across a raw, fresh steak that’sred on the surface, it should be purple in the middle. If you let the steak sit for a bit exposed to air, that color will change, or bloom, to cherry red.) (2) In the presence of oxygen (better referred to as oxygenation), fresh meat blooms and turns its characteristicred color. This form of myoglobin is called OXYMYOGLOBIN. After prolonged exposure to oxygen, (3) we then have METMYOGLOBIN, which appears brown. If you’ve ever been to the grocery and see brown spots on the “Reduced for Quick Sale” fresh meats, those superficial blemishes are METMYOGLOBIN. (Those little brown spots may not look appealing, but may not mean the meat is not safe to eat after cooking. However, if you’veany reason to believe it’s not safe – such as smells spoiled - don’t eat it!) After the meatoxygenates and turns red, it will eventually oxidize and turn brown.

Getting into the chemistry of the matter, the state of the iron in myoglobin (the heme pigment – this is the iron than makes red meat “high in iron”) is a determining factor to fresh meat color. DEOXYMYOGLOBIN and OXYMYOGLOBIN contains iron in the ferrous (Fe 2+) state and METMYOGLOBIN contains iron in the ferric (Fe 3+) state. Let’s dig deeper into this ferrous/ferric business…

Electron management is the key to meat color management. As outlined above, the difference between desirable, red fresh meat and undesirable, brown meat is oneelectron. Yep, one. Follow the arrows in the diagram, and you can see how the different color forms relate to each other. A classic example of these color dynamics in action that you may have observed yourself are the different colors of beef present in one ground beef vacuum chub. Meat may look red or purple on the outside, but have a brown, muddyappearance in the middle. That’s totally okay — look above at the color cycles. The red(bloomed) ground beef was put into a vacuum package, and before it turns purple, it turnsbrown. Since the beef has gone through this natural color cycle a few times (from purpleto red to brown to purple…), the enzymes in the meat that allow for this cycle to continue are worn out (those guys tucker out pretty quickly and easily). Thus, the meat may stop atbrown and stay there. That’s just how the color dynamics work — it does not necessarily mean the beef has gone bad.

I’m working an entry as to why cooked beef color is not a good indicator of doneness, and why a meat thermometer should be used to ensure that any ground meat is cooked to 16o°F. (UPDATED: cooked ground beef color post here) There’s another thing happening in the upper right of the myoglobin color forms diagram —CARBOXYMYOGLOBIN. I’ve left that out of the color dynamics explanation for now, but will address it soon. (UPDATED: Carboxymyoglobin post here)

From "Meatblogger.org"

[h1]Blog Policies[/h1]

Advertising - Advertising is not allowed on wordpress.com hosted blogs. Please do not email me and ask to advertise your product. Furthermore, this is a Pennsylvania State University-affiliated educational blog, not a platform for selling products.

Comment Moderation – As much as I value comments and opinions, comments are moderated for this blog. This is a Pennsylvania State University-affiliated blog and I must work to maintain the integrity and respect of the institution.

Copyright - I have placed this work in the public domain and I disclaim all copyright to the work. I have created this work to benefit the greater good, with specific emphasis on the agriculture community. This work may be freely reproduced, distributed, transmitted, used, modified, built upon, or otherwise disseminated by anyone for any purpose, commercial or non-commercial, and in any way, including by methods that have not yet been invented or conceived.

Please respect the copyright of authors whose material I excerpt for educational purposes. My copyright policy exists for my original work only, not excerpted work from other authors. I make every attempt to clearly identify excerpted works in my posts and podcasts, and if you are in doubt, ask me. I can always be reached at [email protected].

Guest Posts – I welcome guest posts! If you wish to guest post, drop me a note at [email protected]. I ask that guest posts are relevant to agriculture, specifically meat science. Please keep the post credible, research-based, and objective.

Official Communication – This blog does not represent official communications from The Pennsylvania State University or Pennsylvania State University Extension. The views expressed herein and of guest authors do not necessarily reflect the views of The Pennsylvania State University, Pennsylvania State University Extension, or of any other individual university employee.

I reserve the right to amend, append or otherwise modify these policies.